The Effects of Education on Processing Speed: A Longitudinal Analysis of the ACTIVE Study

By Alex McCreight, Hayley Hadges, Ethan Deutsch

March 27, 2022

Introduction to the ACTIVE Study

The decline in cognitive ability common among older adults is known to lead to a decline in the performance of everyday activities and functional independence. Although there is evidence that cognitive skill training can improve cognitive function in older adults, there was no research that indicated that cognitive training results in improvements that persist into later adulthood–this is where the ACTIVE study stepped in. Starting in 1996, the ACTIVE (Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly) trial sought to evaluate whether specific training exercises for cognitive skills such as memory, reasoning, and speed of processing could improve “real-world functional outcomes in later adulthood” (Tennstedt and Unverzagt 2013.)

This study was motivated by the harsh statistics that show low levels of functional independence for individuals of these ages, and the hope that these cognitive interventions would bring about improvements in quality of life, mobility, and health service utilization. The study targeted individuals in good physical and mental health who were also at the age where cognitive and functional decline typically occur, around mid-sixties or older. The individuals were split up into training groups that focused on either memory, reasoning, processing speed, or the control group which had zero cognitive training. Outcome evaluations were administered immediately after the training, as well as at the 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10 year marks after the training. Each training group improved immediately after the first intervention, and the effects were still prevalent at the five-year follow-up (Willis et al. 2006.) Ten years after the study began, 44% of the participants remained, and the only significant difference among the groups occurs in speed as members of the speed group have a much higher mean speed score than the other groups (Rebok et al. 2014.)

Our Question

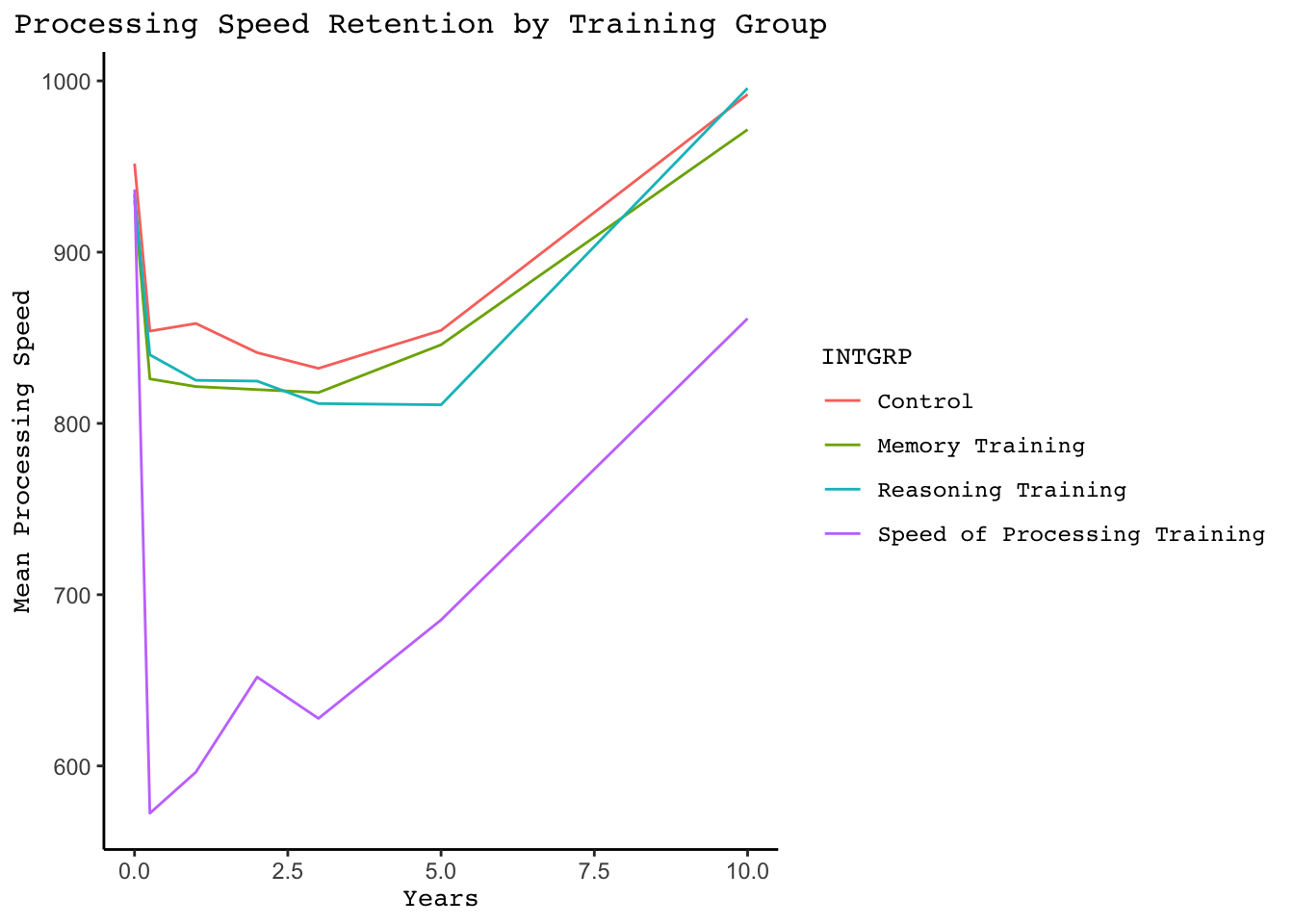

Our analysis focuses on predicting processing speeds based on the available data in the ACTIVE study in order to determine if particular variables make a significant impact on processing speed. While there were multiple variables to choose from such as gender and age, we chose our predictors based on some exploratory graphs of the data. Our analysis utilizes education level, different training groups, and the number of years since the cognitive training to predict processing speed. As shown below in the plot, we noted a distinct difference in processing speed for the processing speed training group before and after the three year mark. The processing speed seems to dramatically improve in the first few years, but after the third year there is a noticeable increase in processing time. To see if this change is significant, we created a new binary variable to distinguish these two time periods in the model.

Figure 1.1

Our Model

Choosing the Model Type

-

Model 1 (Independent Model)

-

Model 2 (Exchangeable Model)

-

Model 3 (AR1 Model)

We utilized GEE to model speed as a function of the speed of processing group (within INTGRP) and had it interact with the number of years each subject participated and the number of years after the first 3 years. We also added a term that takes into account the years of education each subject received and splits them into 3 categories. We used this model and based it on three correlation structures: independence, exchangeable, and AR1.

Choosing the Correlation Structure

Of these three correlation structures, we had to figure out which most accurately reflected our model and we did this by analyzing the the difference between our model standard errors and our robust standard errors. In the independent model, we can see a discernible difference in the model standard errors and robust standard errors compared to the other two models. Of the two remaining structures, the exchangeable model had standard errors about .5 units closer together than the AR1 model showed, indicating that the exchangeable might be a better match than the other two models.

Conclusion

Interpretation

For our model, we have an intercept value of 873.4 meaning that subjects that are not in the speed of processing training group and who only have a high school education or less have a baseline (Years = 0) mean speed of processing score of 873.4. With this as our baseline, we can see that simply being in the speed of processing group will decrease the score by 262.6 points, which in this case is an improvement.

We can also see that over time, disregarding treatment group and education level, the average speed of processing score increases by 3.251 at each check-in (Years = 0, 0.25, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10), which in our case is a worse score. Additionally, we see that over time, scores of the members of the speed of processing training group increase by 32.12 points compared to people in other training groups while keep education level constant. While initially this may seem counter intuitive, figure 1.1 shows us that members of the speed of processing training group have significantly lower speed of processing training scores, so, over time the amount that they increase by will be larger, but their over mean scores are still smaller than those in other groups while keeping education constant.

Finally, when examining the affect education has on speed of processing scores, we see when we hold treatment group and time constant, subjects with a maximum of an undergraduate education level on average have scores 39.3 points lower than those with only a high school education level or less. Furthermore, subjects with a graduate school level of education (17 or more years of education) on average have scores 98.2 points less than those with only a high school education level or less when holding treatment group and time constant.

Limitations

Some of the limitations that we encountered in the data were missing data that might occur from subjects either dying or moving away with incomplete results. We also felt that there were limitations with how we could select the best model because we don’t have an information criterion like we would with a mixed effects model, therefore, we had to estimate based off of standard errors and looking at residual plots.

References

Rebok, George W, Karlene Ball, Lin T Guey, Richard N Jones, Hae-Young Kim, Jonathan W King, Michael Marsiske, et al. 2014. “Ten-Year Effects of the ACTIVE Cognitive Training Trial on Cognition and Everyday Functioning in Older Adults.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 62 (1): 16.

Tennstedt, Sharon L, and Frederick W Unverzagt. 2013. “The ACTIVE Study: Study Overview and Major Findings.” Journal of Aging and Health. Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA.

Willis, Sherry L, Sharon L Tennstedt, Michael Marsiske, Karlene Ball, Jeffrey Elias, Kathy Mann Koepke, John N Morris, et al. 2006. “Long-Term Effects of Cognitive Training on Everyday Functional Outcomes in Older Adults.” Jama 296 (23): 2805–14.

- Posted on:

- March 27, 2022

- Length:

- 6 minute read, 1127 words

- See Also: